Most of the oak woodlands in California are privately owned. The major use of Oak Woodlands is for grazing, primarily for beef cattle. The ranching industry plays an important role in maintaining a sustainable, culturally meaningful, and ecologically rich landscape (Huntsinger and Hopkinson, 1996) in our oak woodlands. Of the many challenges facing ranchers, droughts can be severe.

The great drought of 1862–1865 wreaked havoc on the state and the cattle industry (Burcham, 1957). Since that time we have had severe droughts about 8 times (George et. al. 2010). Even with less severe droughts, cattlemen have a stressful time dealing with changes in forage production. With less forage production, cattlemen either have to reduce herd size, move cattle to other states or locations, or provide extra feed at a great expense. If cattle are sold, it may take several years to build the herd back.

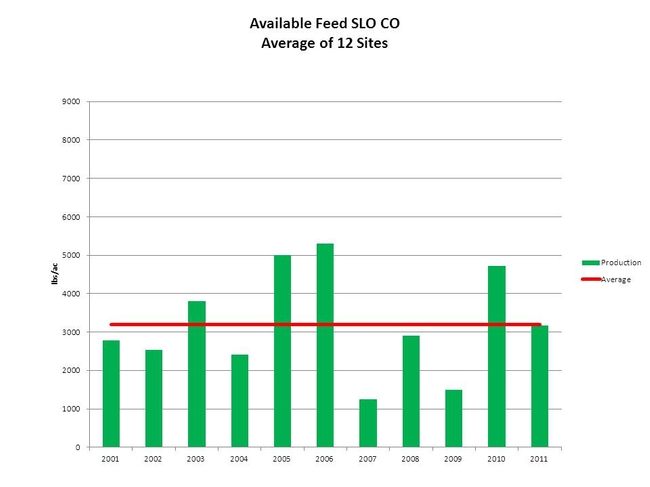

Not all droughts are equal. Droughts tend to be more common in the rain shadow along the Coast Range adjacent to the west edge of the San Joaquin Valley (George et. al. 2010). Even though drought conditions create havoc with management of ranches, ranchers also have to deal with wetter than normal years. There is no such thing as an average year, which makes management decisions very difficult. Forage production and quality can vary greatly from year to year, and is strongly influenced by the timing and amount of rainfall (George et. al. 2001). For example, forage production in San Luis Obispo County over the last 11 years has varied by as much as 4000 lbs/ac (Figure 1). Rainfall amount and timing played a significant role in this variation, which varied by 18 inches of annual precipitation.

Figure 1: Peak Forage Production in San Luis Obispo County from 2001 – 2011.

An average of 12 sites across the county.

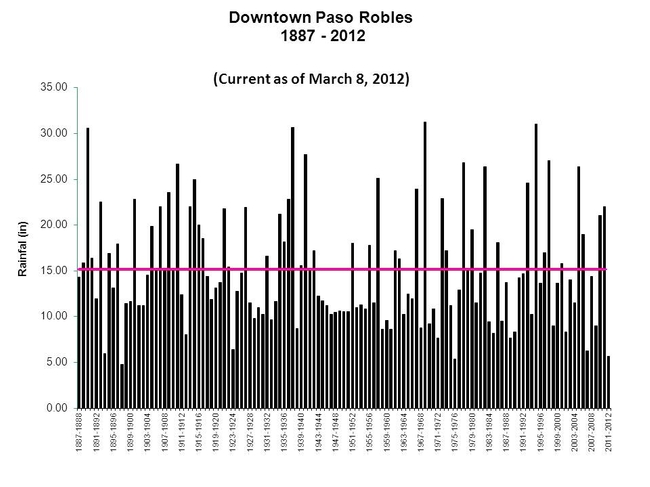

It is just a fact of life that rainfall amount and timing varies. For example, the lowest rainfall recorded in downtown Paso Robles was 4.8 inches in 1898 (Figure 2). The highest recorded was 31.3 inches in 1969, the year of the big flood. It is important to notice that 6 out 10 years are below average (Figure 2). This means that the four years that are above average are usually wet years, which often produces extra forage. For more practical purposes, the years that are below the average determine what and how much forage can be produced on a ranch, which determines the number of cattle that can be grazed on a sustainable basis. It is very important to the ecological health of the oak woodlands / grasslands to maintain proper stocking rates to achieve the desired grazing level. Maintaining the proper amount of residual dry matter (RDM) has become the standard to determine grazing use on oak woodlands and annual grasslands. Properly managed RDM provides protection from soil erosion and nutrient losses, and also plays an important role determining the following year’s production and composition of species (Bartolome et. al. 2006). To accomplish this requires constant change in management by ranchers. I applaud those ranchers who work so hard to accomplish this.

Figure 2: Rainfall records at the down town Paso Robles. Data is based on water

year July 1 – June 30. Average precipitation is 15 in/yr.

Below are images taken of the peak forage production for San Luis Obispo County:

Spring 2006 normal, wet conditions

Soda Lake Site Cambria Site

Spring 2007 drought conditions

Soda Lake Site Cambria Site

References

Burcham, L.T. 1957. California range land: An historico-ecological study of the range resource of California. Division of Forestry, Department of Natural Resources, State of California, Sacramento, California, USA.

Bartolome, J.W., W.E. Frost, N.K. McDougald, and M. Connor. 2006. California guidelines for residual dry matter (RDM) management on the coastal and foothill annual rangelands. Oakland, CA USA: Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources, University of California, Publication 8092.

Huntsinger, L. and P. Hopkinson. 1996. Viewpoint: Sustaining rangeland landscapes: a social and ecological process. Journal of Range Management 49(2):167-173.

George, M.R., R.E. Larsen, N.M. McDougald, C.E. Vaughn, D.K. Flavell, D.M. Dudley, W.E. Frost, K.D. Striby, and L.C. Forero. 2010. Determining Drought on California’s Mediterranean-Type Rangelands: The Noninsured Crop Disaster Assistance Program. Rangelands 32(3):16-20.